How Does Dopamine Shape Our Choices? Thesis Investigates

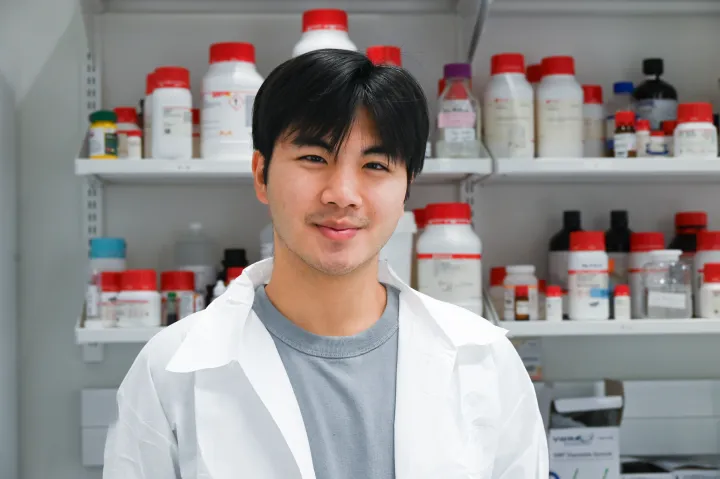

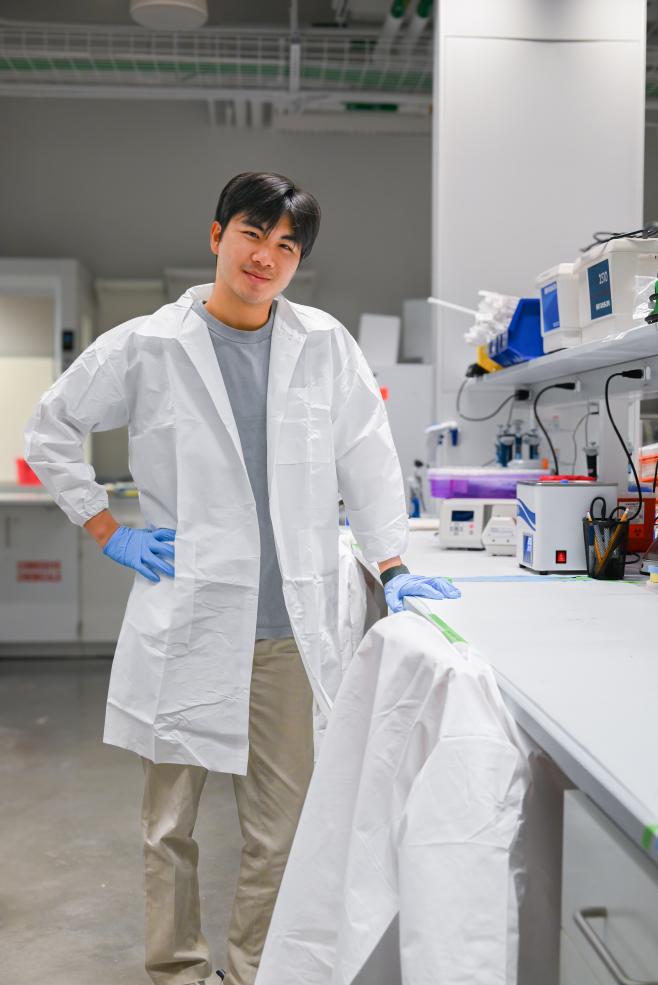

Neurobiology concentrator Sean Meng ’26 is fascinated by how individuals see the world.

Long before his time at Harvard, he attributed this interest to two distinct occurrences.

He first became aware of how differently people can experience the same environment while serving as a teaching assistant at a school in Lawrence, Massachusetts. There, he met Elmer, a first grader with severe autism who was, for the most part, overlooked. After spending more time with him, Meng found that Elmer truly “was seeing the world in very different ways.”

“We would walk down the corridor, and he would point things out to me, saying, ‘Do you hear that? Do you see that? Do you see this door?’” While there was no door, it caused Meng to realize that Elmer was trying to explain the world he was seeing, and let Meng be a part of it. “I became curious – maybe his brain is wired differently and it's producing a different reality,” he explained.

In his second transformative instance, Meng unexpectedly found his high school dorm room neighbor in his bedroom, pouring milk on his floor tile. When Meng asked what he was doing, his neighbor replied, “The voices told me that it would make them go away.” Meng grew up with this neighbor, and when he developed schizophrenia at the age of 19, Meng was able to see his entire progression. “He hears these things,” Meng affirmed. “How does the brain give rise to such different realities and different versions of the world?”

As part of his senior thesis research, Meng is studying the dopamine levels in mice, evaluating how those levels change across ages, and how that reflects learning patterns in mice and humans alike.

He’s seeking to answer the central question, “can dopamine explain the way that an adolescent, adult, and an older person (who may be suffering from cognitive decline and dementia) processes their environment and makes a choice?”

Trials and Answers

How did Sean and his team perform over 3 million trials? An animal, such as a mouse, can perform roughly 300 trials per day. Sean and his team tested roughly 40 at a time, for a 15 day period, then retrained every 2 months for 3 years. Photo by Jeffrey Yang '26

During his work at the Bernardo Sabatini Lab at Harvard Medical School, Meng and his team have conducted over three million trials over the course of three years. Neurobiology Professor Bernardo Sabatini serves as Meng’s principal investigator, and Neurobiology Postdoctoral Fellow Kevin Mastro serves as his mentor.

To study the dopamine levels across different-aged mice, Meng surgically inserts an optic fiber cord into the mouse’s brain, which continuously measures the exact levels of dopamine, allowing Meng to precisely identify when dopamine spikes and when it remains consistent.

The “two-arm bandit task” studies how mice process feedback, learn, and adjust their behavior to maximize their rewards. In this trial, thirsty mice are presented with two ports, where one side is more likely to give water by poking at it than the other side. Then, the reward probability of getting water switches, and the mice must quickly adapt. Meng will continue testing and reporting throughout the remainder of his senior year.

As he approaches his Harvard graduation in the spring of 2026 and seeks graduate training in neuroscience, he hopes to leave a lasting legacy on campus – especially with the campus laboratory he has helped build out since his first year, OpenBio.

The Harvard Undergraduate OpenBio Laboratory aims to democratize access to biological lab work for undergraduate students, providing them with a pathway to create real-life impact for their communities.

Going forward, he strives to connect individuals through science and empower people, each with their own perspectives, to advance the field. He believes that embracing diverse ways of understanding the world leads to a more inclusive science and a clearer truth.

“For me, what is most important is empathy – how do you develop empathy for other people?” Meng reflected. “My solution is to explain it through science, the most grounded, objective source. If people can come to agree and understand science, then perhaps we can disseminate understanding and empathy to our world to make it a better place.”