Three years ago, I wrote one of my first blogs about my academic and personal journey reconnecting with my Ecuadorian heritage and indigenous community. This past winter break, I was lucky to continue this experience of homecoming and travel to Saraguro, Ecuador with the help of a research grant from the Harvard University Native American Program. Both inside and outside the classroom, my journey at Harvard is marked by crucial moments of self-reflection that deepened my understanding of where I come from, where I am, and where I’m going.

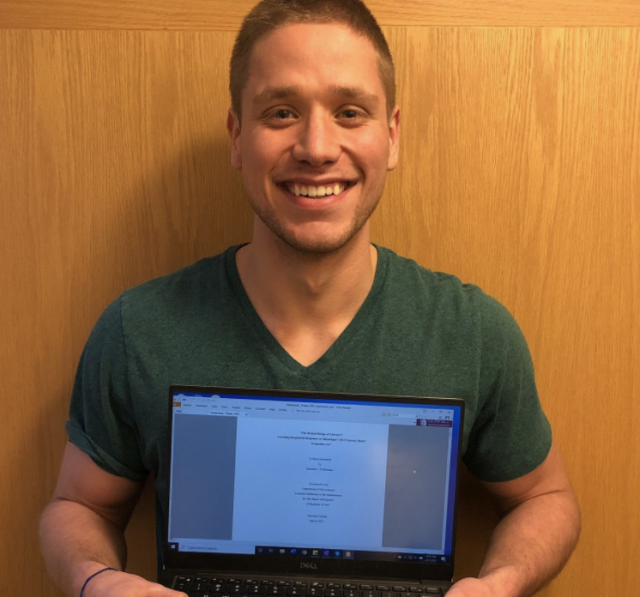

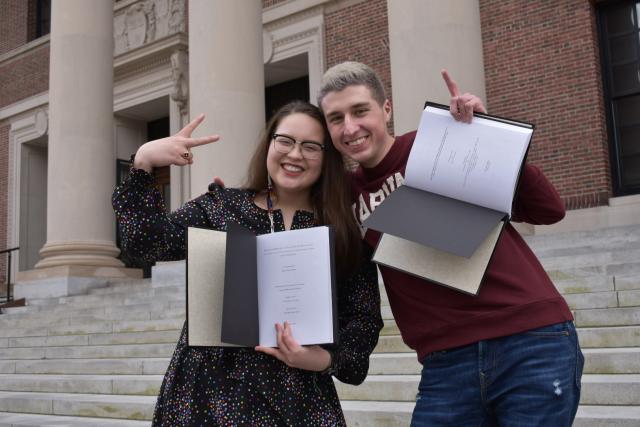

This trip and my senior thesis research project are part of my ongoing commitment to indigenous voices, knowledge, and futures. Students concentrating in Social Studies must write a senior thesis in order to graduate. Each thesis is unique as social studies is a choose-your-own-adventure interdisciplinary field in which students craft a “focus field” of 4-6 classes in different disciplines. My focus field, Indigenous Futurisms in the Context of Late Capitalism: Kichwa regenerations of indigeneity, is an attempt to combine my interests in Latin American studies, Indigenous studies, and critical theory.

At times, it can be difficult to discuss issues in the classroom, from a position of privilege, when our realities in the Global South demand immediate action and advocacy. I bring so much of my lived experience and community-based knowledge into the classroom to give voice to the seemingly abstract ideas we engage with. For centuries, indigenous voices have been silenced in academic realms for not fitting into the standards of what counts or doesn’t count as knowledge. Research is a word that names a colonial wound; for many communities, it has meant the harmful extraction of knowledge for an outsider’s benefit (getting a PhD, writing a book, etc.). With this in mind, I see my thesis as an intentional opportunity to re-write, retell, and regenerate indigenous history for indigenous readers and futures.

My recent trip to Ecuador was the first step in accomplishing such a task, as I dedicated my time to building relationships with networks of indigenous activists in my home community anf other Kichwa communities. My thesis advisor and founder of Harvard’s Quechua Initiative on Global Indigeneity, Professor Américo Mendoza-Mori, helped me build an itinerary by connecting me with Kichwa youth who I could learn with.

Trying out my ability to soplar

Tayta Masaquiza had many hand-made Andean flutes, known as zampollas, which I got to check out. Soledad Chango

I met Kichwa Salasaka violinist and language activist, Soledad Chango. Soledad welcomed me to Salasaka by teaching me about her community’s history and contemporary situation, from the perspective of a young person engaged in cultural reclamation through the Kichwa language. We visited two elders in her community, Tayta Manuel Masaquiza and Tayta Rulfino Masaquiza, who are respected points of reference as knowledge keepers of Kichwa Salasaka history, to engage in intergenerational discourse regarding indigeneity, youth, and the importance of cultural continuity. These conversations were incredibly rich and profound, as transmission of knowledge is how youth can carry forward the lessons learned from hundreds of years of indigenous resistance. As someone who grew up in diaspora, I didn’t have access to learning opportunities with elders in my community (other than my grandparents) in my childhood. I am forever grateful for Soledad’s curiosity and open-heartedness that guided our knowledge exchanges throughout my visit. She will be studying at MIT in the fall, so we will be able to continue this friendship soon!

Hilando en Salasaka

When I arrived at Tayta Masaquiza's house, I was asked to hilar (spin wool) and show my knowledge of traditions. Soledad Chango

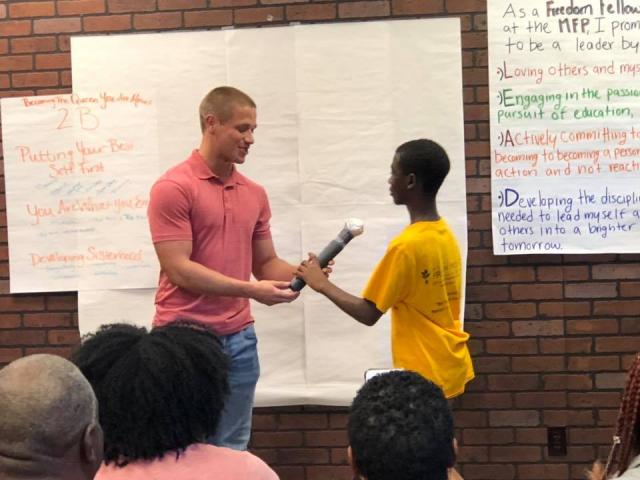

Apart from my visits to Salasaka and Otavalo, I also spent time in the capital, Quito, where I was invited to meet with the leaders of La Universidad Intercultural de las Nacionalidades y Pueblos Indígenas Amawtay Wasi (Kichwa for House of Wisdom), which is a higher education institution run by indigenous peoples and for indigenous peoples. In a class during my sophomore year called Critical Latinx Indigeneities, we read about the decommissioning and closure of the University in 2013 due to failing to meet Western standards. In 2021, the University was re-established as a public Indigenous university and is currently beginning to build its campus in Quito while holding regular virtual programming.

Portrait in Quito

Every trip, I get more comfortable wearing my indigenous clothing with pride in all places, like the capital. Amy Chalan

This university is not only the achievement of years of struggle for equality in education for indigenous peoples, but also a fundamental step in decolonizing higher education by centering indigenous epistemologies and pedagogies. It was an honor to meet with Hatari Sarango, fellow Kichwa Saraguro brother and indigenous rights activist, Pablo Pomboza, Rector of the University, and Ángel Ramírez, Vice Rector of Research. I was able to brainstorm about my thesis project with mentors who understand the fundamental goal of my thesis: to engage in knowledge production by us, for us.

Visiting la Universidad Amawtay Wasi

It was an honor to meet and share my project with indigenous intellectuals at Ecuador's public intercultural university. Amy Chalan

Last but not least, in Quito I also had the incredibly opportunity to meet with Kichwa Saraguro intellectual and renowned indigenous rights activist, Tayta Luis Macas. He is a political leader whose work with indigenous organizations, government, and universities has significantly impacted the life of contemporary indigenous peoples in Ecuador. Tayta Macas is one of my role models and intellectual idols (I even wrote a paper about his writing in my Social Studies junior tutorial), so getting to share my activism and academic work with him was profoundly meaningful.

Tayta Macas is a Saraguro native and he shared memories of his youth that I will honor in my heart forever. He recalled anecdotes about two of my great-great-grandfathers, Tayta Ancelmo Chalán and Tayta Joaquin Vacacela, who are held dearly in our collective memory as fundamental community leaders who protected communal lands and advocated for the rights of Saraguros. Not everyone holds intimate details about how they were in life, as our tradition involves oral history and there is no publicly available written story about Saraguro’s first indigenous leaders. The memories Tayta Macas gifted me touched my spirit with an abundance of gratitude and serenity.

I owe my life to my great-great-grandfathers’ dedication to our community and I honor this ancestral legacy everyday with my passion for knowledge and justice. My mission began many generations ago and will go on for generations to come. To know this is to recognize the interconnectedness of all life and to commit myself wholeheartedly to the protection of all life.

Special thanks to everyone who made this trip possible! I hope to continue this journey over the summer as I continue to write my thesis.