Growing up, I was sold the idea that traveling was a way for me to grow spiritually and intellectually. I was taught to instrumentalize the rest of the world as a site of my education and personal improvements. I was completely intrigued by the novelty of being a traveler, a “global citizen.”

When I arrived on campus as a first-year student, being this “global citizen” was suddenly in the realm of possibility given Harvard’s overwhelming resources. From international internships to summer and term-time study-abroad programs, there are literally hundreds of experiences you can choose from, and many of them are fully funded with financial aid or travel stipends. As a result, more than half of all undergraduate students go abroad at one point or another during their time at Harvard. I, for one, have spent both my college summers so far in a different country—a few months in Belgrade, Serbia (I worked for an NGO focused on non-violent activism/strategizing) and another few in Cape Town, South Africa (where I interned for a grassroots healthcare activist organization).

The biggest lesson I’ve learned from my travels is that the world is anything but my oyster—it is not small and graspable but rather infinitely complex and expanding. Instead of personal growth, I experienced my own shrinking—I was getting smaller and smaller in a world that was getting larger and larger….

I wanted to write this blog post as a counter-narrative to the romanticized vision of travel that seems most prevalent in our culture today. Being abroad is not romantic. It’s extremely difficult and alienating. There’s nothing I can take for granted. Even going grocery shopping takes huge courage when stores are filled with unfamiliar products. Living alone, far from being an indulgence for my introverted sensibilities, is actually quite scary and lonely. Navigating public transportation is almost impossible when I don’t have cellular data and don’t understand the language.

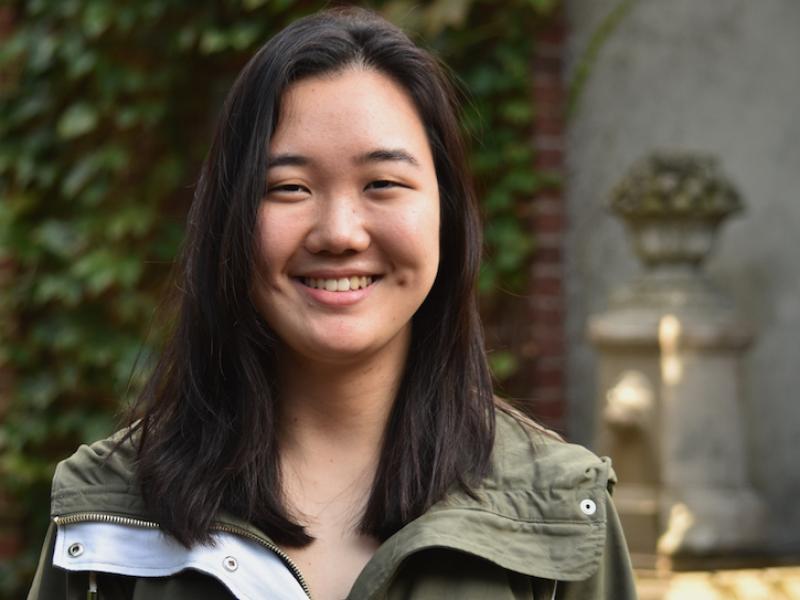

Amidst these difficulties, my hypervisibility as an Asian American woman in both Serbia and South Africa certainly affected my experiences. When abroad, I found myself being especially attuned to how I was being perceived and reached a depth of self-awareness that I hadn’t ever experienced before, even on Harvard’s campus. In these countries, not only was I an Asian woman, I was an Asian American woman and a student from Harvard who had the ability to traverse borders and continents. Navigating weird glances during my 40-minute bus rides to work every day or the more explicit microaggressions and comments on the streets forced me to critically evaluate my identity and the ways it was being interpreted.

A graffiti wall a bit outside Belgrade, Serbia reads "Yankee Go Home"

Cayla Lee

Though unpleasant, in many ways these various interpersonal interactions helped me make sense of the world. I learned about these countries’ histories and cultures through not just museums and books, but also through an awareness of how others perceived me and my body. For example, how I was treated in Serbia was very much related to the ethnocentric nation-building that took place after the Yugoslav Wars and the incredibly destructive NATO bombings of Belgrade, whose visceral reminders were scattered throughout the city in the form of preserved bombed buildings and advertisements to join the Serbian military. My experiences in South Africa could not be divorced from the extremely complex racial politics of the country’s post-Apartheid present and neocolonial interventions in the country. In other words, I could not understand my personal experiences without also coming face-to-face with the global structures of power that were at play. On the flip side, I also couldn’t really understand various histories without having personal, embodied experiences in them. In this way, my experiences abroad were not departures from or extraordinary experiences in relation to the rest of my Harvard experience. Going abroad was a way for me to learn through a different methodology—one that was more embodied and direct—the hard concepts we were grappling with in my Anthropology, History, and Social Studies classes.

I’m cautious here not to replicate the notion that the rest of the world is a site for me, a privileged traveler from the United States, to experience a kind of intellectual or spiritual enlightenment. The truth is, traveling abroad gave me anything but intellectual or spiritual clarity. Rather, it worked to make me hyper-attuned to the complexities of my identity and the different ways my presence could be interpreted within different geographies and histories. It threw me out of my comfort zone and made me think really critically about my place in this world, a positionality that cannot be separated from the global conditions I’ve been born into. It also challenged many of the clear-cut theories I had learned in my classes. The explanatory power of social theory seemed to fall apart when put side-by-side with the immense complexity of the world. I was confronted with the limitations of the worldview I had developed from within the gates of Harvard. It seemed impossible to be a “global citizen” when I ran into the problems of my difference and hypervisibility as an Asian American woman.

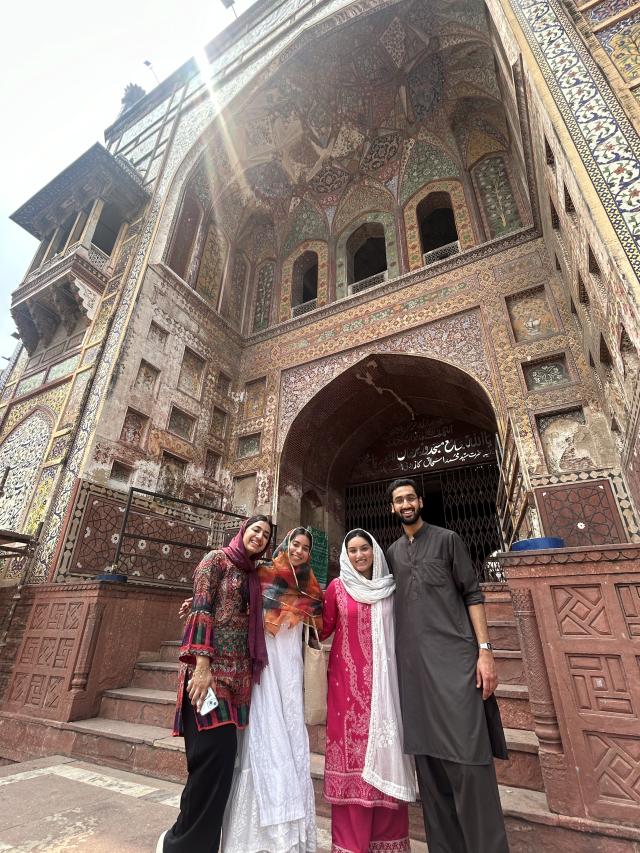

A coalition of activists organizing around anti-gentrification, universal health care, public transportation, decolonizing education and more protest in front of the parliament building in Cape Town, South Africa

Cayla Lee

In these ways, my experience abroad was truly transformative in incredibly challenging ways, and I’m so grateful to have had opportunities to travel—a privilege I would not have been given had circumstances been different. However, going to Serbia and South Africa turned out to be valuable in very unexpected ways. For instance, I did not grow, but rather shrunk in relation to the newly-realized enormity of the world. Also, instead of solidifying an understanding of myself, my travels revealed how my identity was multiple, infinitely complex, and historically/geographically situated.

This journey, however, did not start and end with my summer breaks. Rather, it started from the moment I left my home in Seattle to come to Harvard or perhaps even much before. Every experience I’ve had, every encounter with my identity and others’, have forced me to grapple with challenging ideas and histories. Being at Harvard as an Asian American student has been a constant act of navigation and self-situating (temporally and geographically), and this trajectory was merely accelerated by my time abroad. As many of you consider leaving home to attend college, to travel, or to have other new experiences, I hope this opens you also to the possibility of surprises and counter-narratives that emerge from the multiplicities of the world we inhabit, and I hope you are able to find something poetic in the midst of this enormity.