The recent pandemic has made connecting with Harvard’s traditions difficult for undergraduate students. A canceled Harvard-Yale, limited access to Widener, or the multitude of other things that were restricted from students made it challenging for students entering the College to experience all that Harvard has to offer. This disconnect includes the Harvard underground tunnels, yes, the ominous tunnels.

If you’ve ever heard about Harvard’s underground tunnels, you may be aware of a legend or story associated with them. It may have been a story of politicians being protected by them to hide from student protests, a story about them serving as bomb shelters for students, or any number of stories that can be overheard as students discuss the tunnels. Often depicted as a black hole full of secrets, the tunnels fill student’s minds with curiosity and creativity. Although Harvard’s underground tunnel system may be deemed the most obscure part of the University, students can interact with them on any given day.

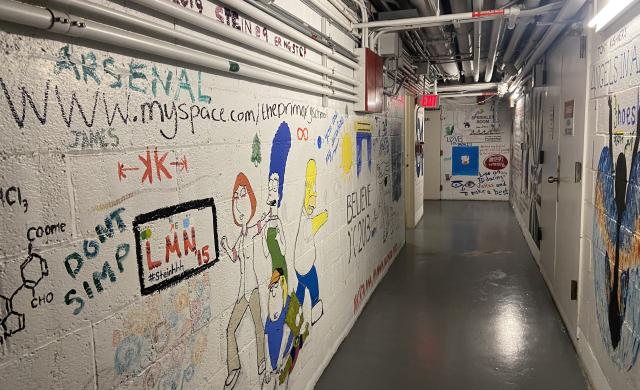

“Students use the tunnels to get from point A to point B within Adams. For example, you can go from A Westmorly to B Westmorly using the tunnels. They connect different parts of Adams,” says Grace Seifu, a second-year resident living in Adams House. “There are some really cool paintings near the laundry room. It’s very colorful and vibrant there, and less scary than some of the other parts. Some of the scenes that you can see on the wall are very nice.”

Adams House isn't the only place where tunnels can be found. Other undergraduate Houses such as Eliot and Kirkland have access points to the tunnel system to keep students connected. The tunnels not only connect students from one entryway to another, but they also connect students past and present.

Ebony Smith, Eliot House’s HOCO co-chair says, “If you're a senior on the night of housing day, you're supposed to come down here [to the tunnels] with your friends in secret to paint on it. It's encouraged, you come down here, you paint something and it stays forever. There are even intentionally unfinished sketches of things that previous seniors have left for us to finish. They are intentionally left unfinished to have that community bond. It's also a tradition for alumni to come down and finish something that they never finished or to draw something new.

In addition to being spaces for traditions, the tunnels serve as home to communal spaces. A rowing room, gym, movie theater, and dance studio are all located within Eliot’s tunnel system. Eliot’s laundry room can also be easily accessed via the tunnels.

But the tunnel system extends beyond the Houses, in fact, it extends throughout Harvard. The main tunnel system stretches from the Business School to the Law School, and the majority of the system cannot be accessed by students. If they’re not for connecting students or displaying art, why does Harvard have these tunnels?

The tunnels emerged as a way to power the University in the late 1910s. The predecessor to the MBTA, the Boston Elevated Railway, powered its transit lines with power stations. One of those power stations was where Eliot House stands today. The power station would generate electricity and as a result generate heat waste. The University bought the heat waste from the Railway and ran pipes up to the Yard as Widener was constructed. The tunnel system emerged as a way to protect the pipes heating the University.

When Eliot House was built the University ran the piping to Blackstone Steam Plant, which has been feeding the campus since the late 1920s. The tunnels that feed in from Blackstone are 8 feet wide and 8 feet tall throughout most of the system, and their walls are lined with pipes that carry steam out of the plant and water back into the plant. Three large pipes that carry steam toward campus to heat it. When the heat is removed from the steam, the water condenses and is sent back to the plant through two smaller pipes. It is then reheated and sent back to the University, in a constant recycling process.

Once the interconnecting highway between the buildings was established, it became useful for other reasons. Typically, when pipes are run through the soil, they have a lifespan of roughly 40 years. The tunnels extend their lifespan by two to three times that. The tunnels that run from Blackstone are over 90 years old, and the ones that run from Eliot House are over 100 years old. This is in part because the pipes can be maintained without breaking ground, and minor issues don’t become large ones. The system is also used for other purposes, such as telecommunications.

These tunnels serve as the University’s backbone in more ways than one. Not only are they the heart of the University’s power, but they are also the heart of many rich Harvard traditions. If you have the opportunity to trek down to Eliot’s or Adams’ tunnels, I highly recommend that you do. On those walls you’ll see marks that represent students past and present. Maybe one day one of them will be yours.