Today, I’m a proud Latina and indigenous Ecuadorian.

Despite the fact I grew up in the US, I was born in Ecuador. My experience growing up undocumented limited my ability to feel connected with my Ecuadorian roots and I had trouble feeling proud of my heritage. Everything changed last year: I was finally able to visit Ecuador and Harvard’s academic offerings allowed me to finally learn about myself and my people.

My family immigrated to the US from a small, indigenous village in the Andes mountains called Saraguro. I was born in the capital of Ecuador, Quito, and came to the US with my mom when I was almost 2 years old. My grandparents were in the US at the time, having immigrated to NY in the mid 90’s. Despite having been in the US for 25 years, my grandparents and family are very proud of our indigenous identity and keep indigenous traditions and a bit of our language present in our household. Growing up, we dressed in traditional clothing for celebrations with other Saraguros and stayed connected to our home far away, but I had a hard time feeling proud and sharing this part of my identity with my friends throughout my life; I didn’t want to feel different and didn’t completely feel my own connection to Ecuador. This changed completely during my first-year at Harvard.

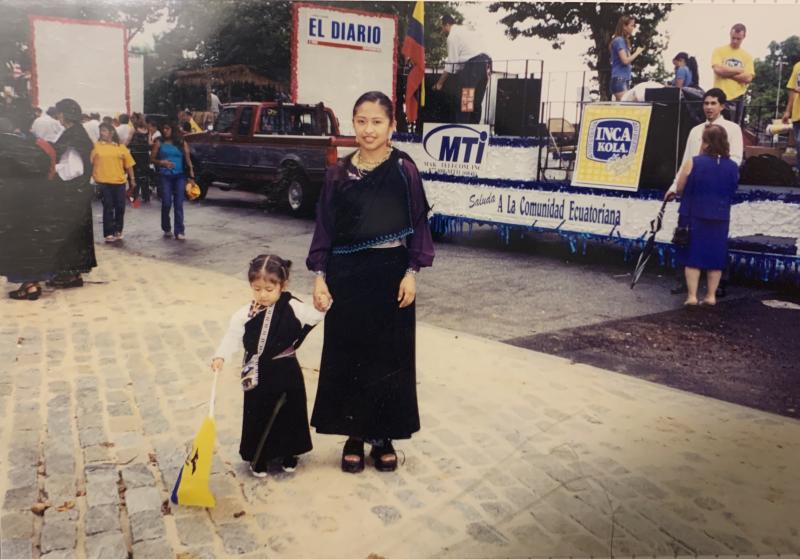

My mom and I dressed in our traditional clothing at an Ecuadorian parade back in the day.

In my first semester of college, I took a freshman seminar on Amazonian indigenous people with the Anthropology department and it opened my eyes to a world I had never experienced before. In high school, I had loved science because I excelled in it and felt comfortable, but I had never considered taking a class to learn about my indigenous identity.

During my winter break, I visited Ecuador for the second time ever and stayed for 3 weeks. Having grown up undocumented, every time I travel, I feel incredibly grateful for the ability to leave the US and experience new atmospheres. During my time in Ecuador, I felt like I learned more about myself than I ever had before. I met family members who had seen me grow up through pictures on Facebook, learned about traditions and their roots in our Incan ancestors, and explored Ecuador from our small town to my birthplace of Quito.

My family worked in agriculture in Saraguro in the mid 90's before coming to the US. This is a photograph they capture of a typical day of work.

My father’s family invited me to spend Christmas with them in Saraguro to experience the Andean celebrations that originated before the Spanish conquest and pay homage to our Incan ancestors through games, dances, parades, and parties that symbolize reciprocity and the importance of community. During this period, the central figure of the celebrations is the markantaita, (chief father), who is chosen by each community and gets the privilege of housing the figure of Baby Jesus until Christmas Day. In Saraguro, Catholic beliefs like Christmas are intertwined with rituals and parades in Quechua, the language of the Incas, to create a unique hybrid of Christmas. Instead of following typical consumerism and exchanging material gifts, markantaitas host communal gatherings, called mugunas, open to everyone and feed every guest at no cost in exchange for their company.

Serving dessert, miel (honey), at my family's muguna.

This winter my great grandfather was the markantaita, meaning our family had the honor of hosting the mugunas and celebrations. The mugunas were one of my favorite parts of Christmas in Saraguro because I was able to meet people from our community who grew up and knew my grandparents and mother before they immigrated to the US. I also admired the way mugunas were a sort of gift exchange, by symbolism of reciprocity because everyone gathered to be served food and to collectively respect the markantaita and share religious beliefs. No one in my town was talking about their expensive Christmas present from their uncle, or the present they bought for their sister, because Christmas was not a celebration of material goods and the satisfaction of getting objects, but instead, a shared experience that everyone contributed towards in some way.

My great grandparents let me carry the statue of baby Jesus for a little bit during the procession to the church in town. It was a great honor to do this!

During the procession on Christmas day, I got a photo with two quiquis, who are playful characters that cause mischief throughout the holiday season and don't reveal their identities until the end of Christmas.

I also visited my maternal grandfather's 2 fincas (farms), where he has livestock and cultivates fruits and vegetables. My grandfather lives with me in the US but always sends remittances to our family in Ecuador, who take care of the farms and animals until my grandfather returns someday. It was amazing to finally see in person the reason my grandfather works so hard and he was really happy. I liked spending time walking through the farm in the mountains.

Although I’ve grown up hearing stories from my family about what it was like to live in Saraguro, nothing compared to the actual experience of walking through my town and finally feeling like I belonged and I was home.

Another of my favorite memories was during the Dia de los Reyes (Three Kings Day) parade on the very last day of celebrations, when my family and I accompanied my great-grandparents as we walked to the church in town. We were surrounded by a full band playing traditional music, kids and adults dressed up and dancing traditional-style, and other community members walking to honor the holiday and our family for hosting the festivities. Having woken up before dawn to participate in pre-procession traditions, I was tired and uneager to walk the distance to the church in heels, but it was during the parade that I reflected on my experiences the most.

Here I am with my cousins Katherine and Yareli. For Dia de los Reyes, my family dressed up in matching sets of traditional clothing because we had the honor of hosting the festivities.

When my mom left Saraguro in 2001, she was 18. Many years later, at the age of 18, I was walking through the same cobblestone streets my mom painfully left behind, thinking about the courage she had when making the decision to immigrate to the US. I’m so grateful for the opportunities and blessings the US has given me, but couldn’t help to imagine what my life would have been like if I stayed in Ecuador. What would it have been like to grow up so close to my extended family? Would I have different passions and aspirations? Would I be the same person? I don’t have answers to these questions and never will, but I realized the only way I could understand the history of my Incan heritage, my family’s own past in Saraguro, and myself as a person was by exploring Ecuador, both physically and through research and reflection on my own.

My mother when she was in her teens living in Saraguro.

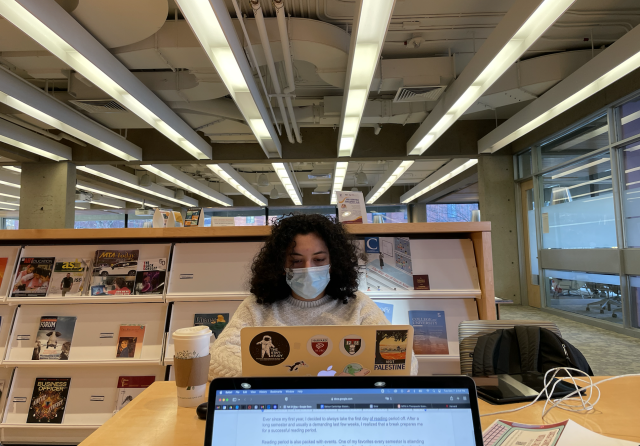

I returned back from my trip to start my second semester at Harvard and knew something essential to me had changed. I thought I had my classes picked out, because I originally wanted to be a biomedical engineering concentrator. I knew the classes I would take to follow that path, but my heart was telling me to let that plan go and choose my classes based purely on my interest in the material. I’m so grateful I took that leap of faith, because the 4 classes I decided to take completely changed my academic direction and changed me as a person.

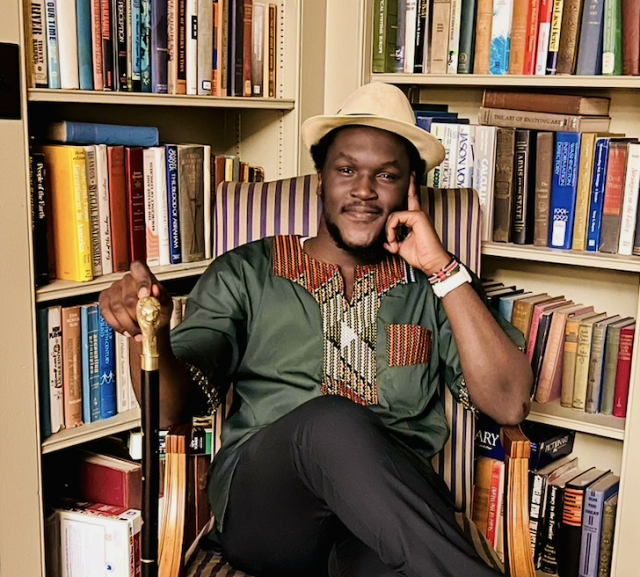

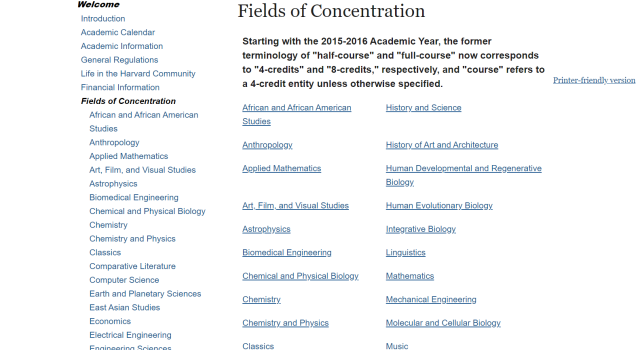

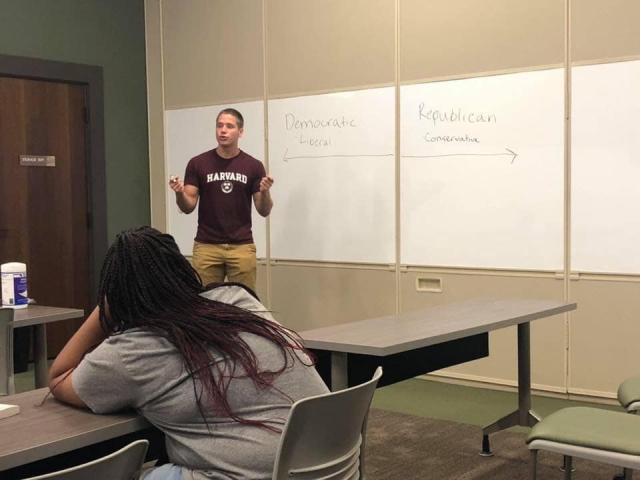

At Harvard, I was finally able to take classes about my own history and identity.

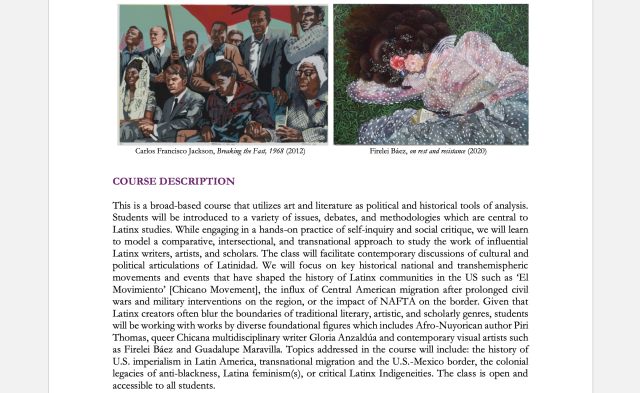

I took a class entirely dedicated to the history of the Incan Empire to learn about my ancestors and indigeneity, a sociology class on US immigration policies to understand the history of laws that shaped my experience as undocumented, a class about Latin American history from pre-colonization until modern times to get a new perspective on important moments in history, and an anthropology class on the US/ Mexico borderlands and Latinidad, with the amazing Profe. David Carrasco, to learn more about my Latinx identity and the relationship of Latinidad and immigration.

These 4 classes made my second semester incredibly monumental and eye-opening. Every indigenous tradition I had grown up doing but also questioning why, finally made sense when we learned about their purposes and meaning to the Incas. The other 3 of my classes also perfectly complemented each other. I was able to learn about Latin America throughout the last few hundred years, how it relates to the Latinx immigrant experience, and how all these elements relate to my personal identity. I even showcased and analyzed my family’s migration story as my final paper for Profe. Carrasco’s class. In high school, I had never even thought about taking classes about my heritage, because I didn’t know they existed. Finally, at Harvard, my classes made me feel like I was discovering my true passions and frankly, discovering myself as an indigena and Latina.

My little cousin, also named Amy, was chosen to be a dancer for the festivities. She practiced for months leading up to these celebrations and performed in front of the church when the procession arrived.

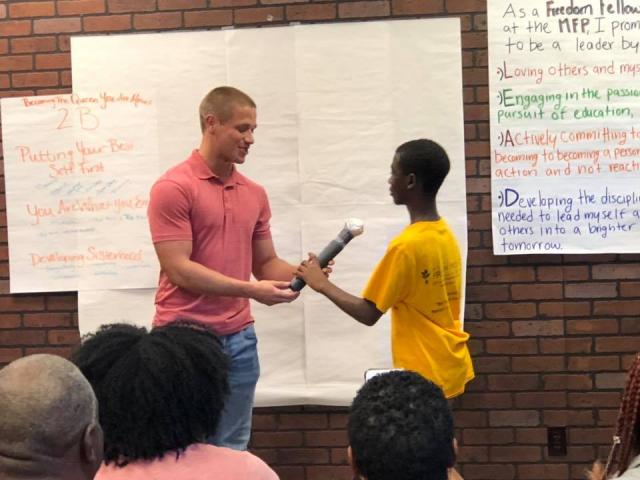

I often use the knowledge I learned from these classes and my experience in Ecuador to inform the decisions I make and the way I am. I still have so much left to read, discuss, and discover and plan on being a social studies concentrator focusing on Latin American economic development and indigenous communities. In the future, I plan to return to Ecuador and organize with indigenous communities to ensure our population is supported and represented in government.

On the plane ride back from Ecuador, I cried thinking about how much I would miss that feeling of belonging, community, and love I felt in Saraguro. Although I began to feel those positive feelings in the classroom at Harvard, when I learned about my past and culture, I promised myself I would go back soon and continue to learn about my family and explore my indigenous and Latina roots. I don’t know when I’ll be able to return because of the pandemic at hand, but I know in my heart that when I return it will be amazing.