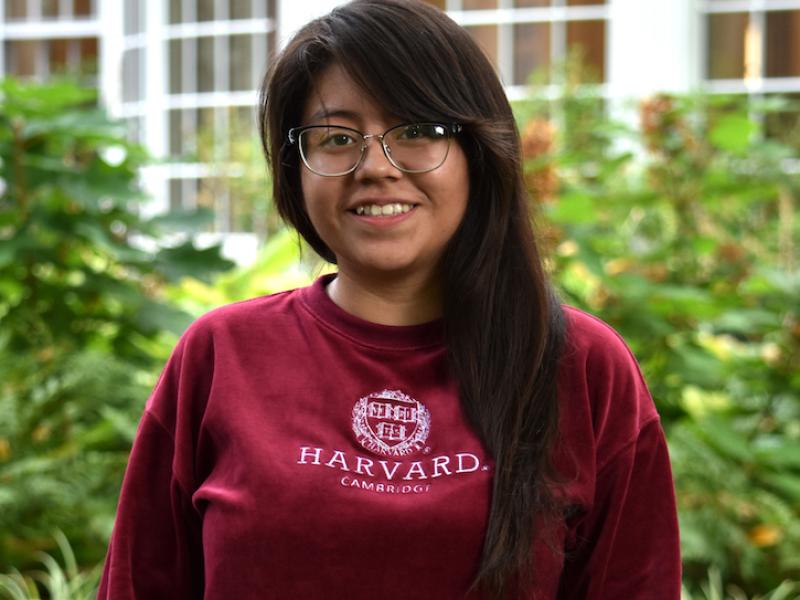

Hi everyone!

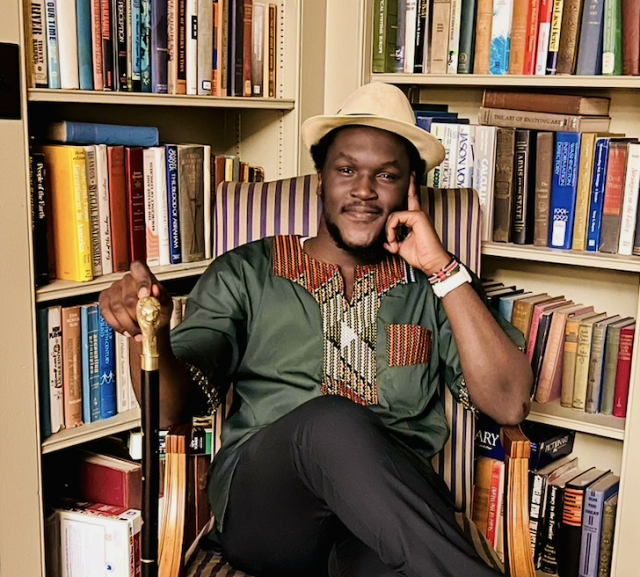

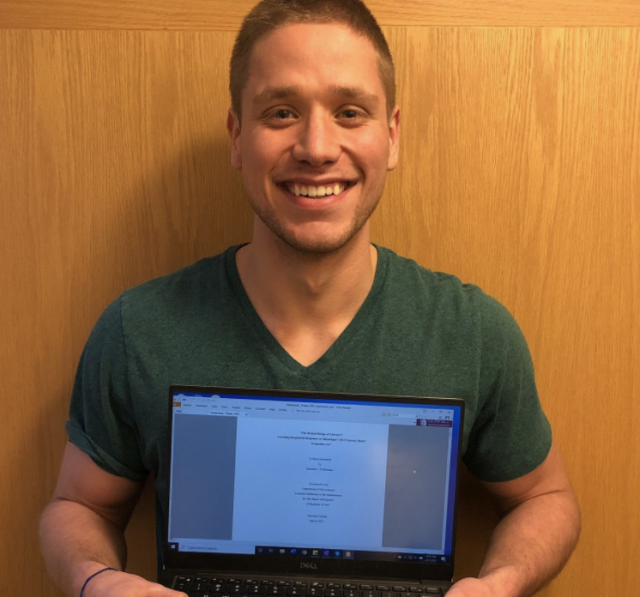

This is Chicken Nugget.

He was born yesterday and will be joining his family of one hundred fellow chickens once he is strong enough to keep up with the older chicks. Freshly hatched and ready to take on the world, I thought it’d be nice to tell him a bit more about our family’s roots.

Meet Chicken Nugget!

We helped him and his siblings hatch out of their shells.

My parents are both immigrants from Mexico, and they’ve instilled in me a strong love for Mexico. However, my family couldn’t save up enough money to have us visit Mexico, so it was hard to have as deep an understanding of our roots as they wanted. My parents would often tell me elaborate stories about their childhood: growing up herding sheep and goats, hunting and gathering food and materials, learning the arts of Oaxaca (like embroidery), and the beauty of community in impoverishment.

There’s not much in history books that could help me understand my heritage more than the stories of my parents.

There are no pictures, as they had to leave them all behind. I can’t look up “my parent’s childhood memories” on the internet. The only clue I have to the beautiful arts they would tell me about a handkerchief my grandmother sent to me from Oaxaca when I was born––completely and beautifully hand-made.

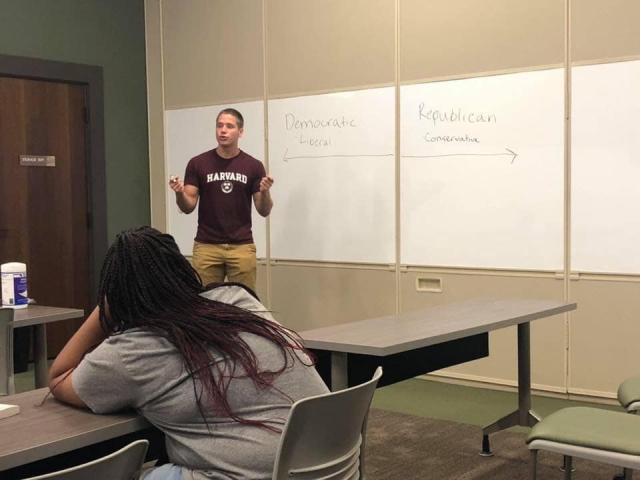

The first time someone identified something more behind my Mexican identity was an Anthropology professor at a summer program I went to during my junior year of high school. Upon learning that my family came from Oaxaca, he asked me what dialect I spoke. He didn’t pry any further when I admitted I wasn’t sure what he was talking about, but I vaguely remembered that the word “Sapotec” floated around my family from time to time.

“We only speak Spanish, I think.”

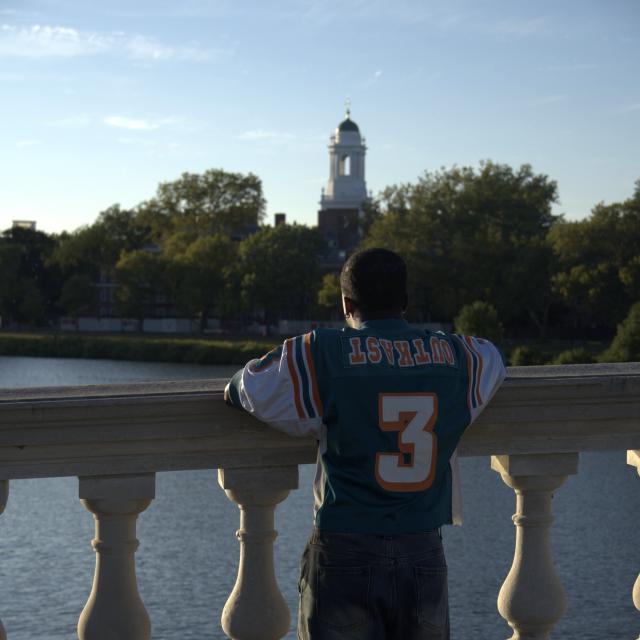

That professor was the main reason I applied to Harvard; after the summer program ended, he told me I had to go to Harvard (thank you professor). A year later, during my freshman fall semester, I took an Anthropology class with Dr. David Carrasco called “Moctezuma’s Mexico: The Past and Present”. He was charting a map of the Aztecs and Mayans, as well as other indigenous civilizations. I noticed that something was off about the area where my family originated. We weren’t Mixtec or Mestizo, but lived in these strongly indigenous areas. I felt something in me shatter when I looked up the word “Sapotec” (Google corrected it to Zapotec) and found out it describes an indigenous pre-Columbian civilization that flourished in the Valley of Oaxaca in Mesoamerica.

We were indigenous. I am indigenous. And I didn’t know.

Thanks to scholarships and jobs, I was able to save up enough money to go to Mexico to see my family and grandmother for the first time last summer. I needed to see who I am. And it was beautiful.

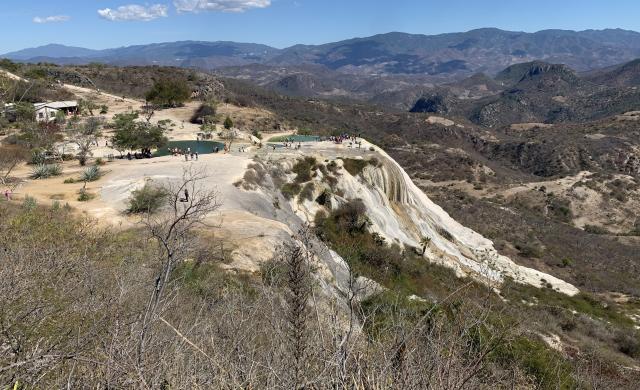

San Juan Evangelista Analco

My mother’s home village in the mountains.

The stories were true. My parents told me that they lived in the mountains. They herded sheep and lived communally. They lived not in the well-known Villa de Etla, but in the Sierra Juarez mountains of Mexico. It was very recently paved, for better transportation, but it still takes five hours to get to the villages at the top. They had great monuments for figures who fought for indigenous communities. Neighborhoods depended on each other. And my family welcomed me home with tears and unfamiliar words in Zapotec.

I had worked on my Spanish, so this reunion would be perfect, but instead I was wondering if I deserved to identify myself as indigenous, as I wasn’t able to keep up with Zapotec language. Upon realizing this, my whole family came together to teach me as much as they could. We visited so many sites, but I won’t forget visiting Monte Alban.

Monte Alban

The playground my uncles and father played on––it’s now a historical site anthropologists are trying to preserve. The local guide was telling us that he was dedicating his life to preserving the history of his––our––community:

“We don’t have our histories and languages documented in the computers. Many small indigenous communities are facing extinction, including mine. I am proudly Zapoteco, which is why I like to practice the language as much as I can, even though it is dying.”

When I came home, I unleashed “fury” on my parents, asking them why they never told us straightforwardly that we were indigenous. They simply responded that they didn’t think it was very important, since they came here when they were eighteen and needed to forgo much of their identity in order to survive in America. I was broken-hearted until they showed me that they had taught me Zapotec customs in small everyday increments all along. I knew how to embroider, how to basket-weave, what clothes we wear, what communal traditions we follow, etc. Even the fact that we wanted to raise free-range chickens had roots in Zapotec culture. I felt more at ease, but one thing was missing.

“What about the language?”

“Being Zapotec doesn’t mean just language. It’s in your blood. But we can continue to teach you Zapotec, if you’d like.”

“Continue?”

“Mija, words like 'cutsi' aren't Spanish. It’s mountain-talk. We’ve been teaching you mountain-talk for years, we just never explicitly said it was Zapotec. You don’t have to prove anything, it’s in your blood. It's who you are.”

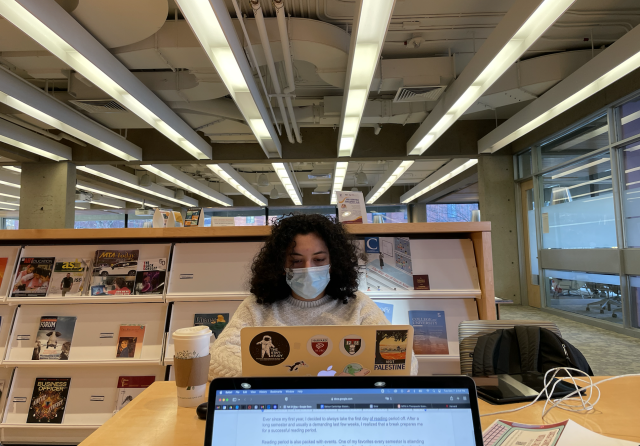

I wouldn't have discovered this integral "missing" piece of my identity, if it weren't for the academic path I chose to take. It pushed me to question and explore the world––and my world in turn.