On October 15th, 2022, I competed in an indigenous beauty pageant and was elected Reina SarUSA 2022-2023.

This experience was a crucial part of my eternal process of remembrance, which I began to share through a blog post written at the end of my first year at Harvard: The Past, Present, and Future: Exploring My Roots in Ecuador. At the end of this blog, I shared my dream of centering my academic studies in Latin American indigenous communities, learning more about my indigenous identity, and returning to Saraguro to contribute to the indigenous movement. Looking back on this post as a senior, I can proudly say that I have taken another step towards completing this goal!

While I grew up in the suburbs of New York, I was born in Ecuador’s capital, Quito. My family and I belong to an indigenous community nestled in the Andean highlands called Saraguro. As people of the Kichwa nation, we share a rich collective history and knowledge, referred to as la cosmovision Andina (Andean cosmovision).

The Andes Highlands of Ecuador

I took this film photograph of Saraguro from the highest lookout point in our town, Taita Puglla. We refer to this mountain as taita, the Kichwa word for elder or father. Amy Chalan

Saraguros maintain customs such as the Kichwa language, traditional dress, creation of crafts and textiles, ancestral plant medicine, rituals and celebrations, traditional food and drinks, music, dance, oral histories, and a community-based lifestyle. Saraguros have also maintained their agricultural lifestyle for centuries and are well known for cattle farming, dairy production, and textile production. Within the context of systemic marginalization and anti-indigenous culturecide, Saraguros have resiliently protected and strengthened their unique way of life focused on community, reciprocity, and solidarity.

Saraguros celebrating Easter

In our pueblo, indigenous traditions are incorporated into Catholic holidays such as Easter. Pictured above is an annual procession held on Easter Sunday. Amy Chalan

At a young age, I could sense that I was different from my classmates. My life at home was reminiscent of Saraguro and culture in the Andes: I grew up eating mote con queso (corn and cheese), watching my grandfather make chicha (a fermented drink native to the Andes), listening and dancing to chaspiska (a music style specific to Saraguro), and learning from my family's oral history.

Although we did not wear our traditional anaco, pollera, and sombrero de lana on a daily basis and we were far from our homeland, my family taught me that we would always be indígenas, as this identity came from within. Anytime that I was physically hurt or emotionally down, my grandfather would remind me that I could survive anything because I was a “runa dura”. Runa is the Kichwa word for person, often used to refer to indigenous people.

Runa dura

Throughout my childhood, my family instilled Saraguro customs, values, and ways of knowing into my imaginary. Amy Chalan

My relationship with my indigenous identity was troubled by the fact that I was undocumented until my high school graduation. I attended a predominantly wealthy and white middle and high school, which cultivated an environment of privilege that led me to feel like an outsider. To be seen as different threated to reveal my undocumented status, so the most comfortable solution for me was to assimilate, work hard to prove that I was an immigrant worthy of being in the US, and maintain my indigenous traditions within the confines of my home.

I grew up attending SARUSA celebrations with my family and was able to partake in bailes or communal celebrations, yet often, my grandfather had to offer me allowance to wear my traditional Saraguro clothing because I had grown embarrassed of my difference. I know now that this feeling is not uncommon and reminiscent of our experience back home, where indigenous nations were displaced, marginalized, and dehumanized as part of Ecuador’s nation-building project.

Posing at the annual Ecuadorian parade in NYC

My family and I attended the Ecuadorian heritage parade in NYC every year, in which we sometimes had a float dedicated to immigrants from Saraguro. Amy Chalan

Every fall, Saraguros living all over the US gather for one night to celebrate our community and elect the Reina “SarUSA”. This event is typically organized by SARUSA, short for Saraguro Residents in the United States of America, which is a non-profit organization that encourages the continuation of our indigenous culture and traditions. The role of the reigning queen is to work with the board of directors to promote the wellbeing of our community, play an active role in events organized by SARUSA, and collaborate with other Ecuadorian and Kichwa efforts. These events range from cultural celebrations such as Inti Raymi, to Ecuadorian traditions such as Ecuavoley tournaments and political events that promote voting in Ecuadorian presidential and congressional elections. In the past, Reinas have organized summer camps for Kichwa youth, fundraisers for SARUSA, and visited Saraguro for annual independence day celebrations, known as Diez de Marzo.

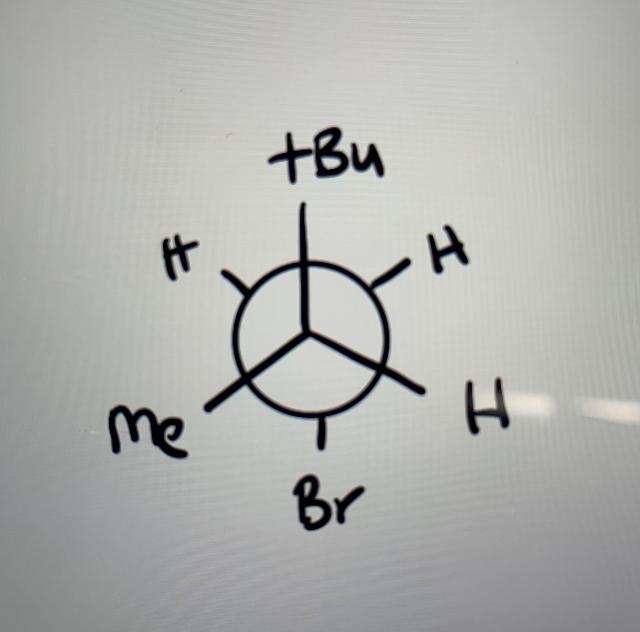

When I was 18, my tía Ziola asked me to participate as a candidate in the upcoming election of the Reina. I respectfully declined. I was not too fond of the spotlight at the time and preferred to keep my focus on my soon-to-begin journey at Harvard. Little did I know that my experience at Harvard would be transformative in terms of uplifting and strengthening my indigenous identity. This year, at the age of 21, I finally decided to sign up for the beauty pageant as a candidate for Reina SarUSA 2022-2023. I was surprised to learn that this goal would require months of knowledge sharing and rigorous preparation for the two major components of the pageant: el hilado del huango (to spin thread from lamb’s wool) and an oral presentation in Kichwa and Spanish.

First, I had to learn how to hilar el huango; a skill practiced by indigenous women in the Andes, in which lamb’s wool is spun into yarn to be used for textiles and daily attire for both men and women, such as ponchos (woven cloak), anacos (traditional skirts), and cobijas (blankets). Before being able to hilar, the wool must be washed, dyed, and escarmenada (thoroughly cleaned and combed). To hilar is to a skill to master, as spinning various fibers to bond and produce a continuous strand of desired thickness is challenging! To make thread that can be used for ponchos and anacos, the hiladora (spinner) must be very skilled, while yarn for blankets and cloths are thicker and easier to make. For the pageant, each candidate had to hilar for 5 minutes and were graded based on the thickness and quality of the thread. This tradition is considered somewhat antiquated, now that people typically buy their clothing rather than make it, but is still crucial to our identity and past as Saraguro women, since self-made clothing was crucial for survival in the cold Andean highlands.

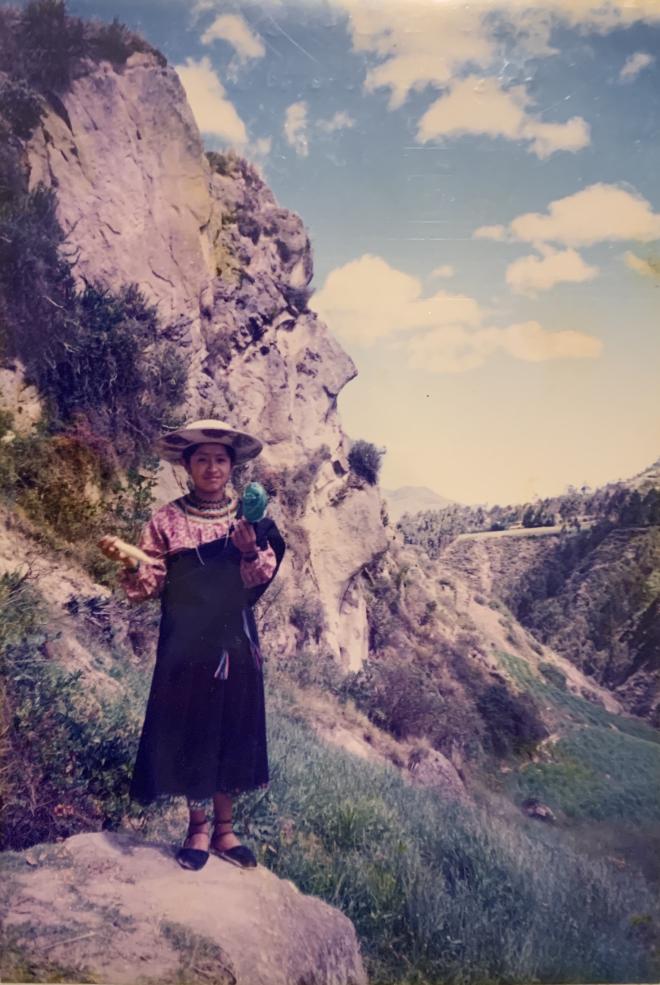

My teenage mother in Saraguro

My mother, pictured in traditional Saraguro dress, is holding a huango and spinning thread. Amy Chalan

My tía Ziola was raised in a family of hiladores (spinners) and began spinning at a young age. In the weeks leading up to the pageant, the women in my family gathered to learn how to hilar under her guidance and help me become the best hiladora possible. This journey became an intergenerational process of knowledge sharing and healing for all of us involved. While my grandmother taught my mom how to prepare the lamb’s wool, my tía Zoila taught me how to make a huango and how to begin spinning wool. I would get very frustrated at first, since it requires careful coordination between both left and right hands, something I was not used to.

Posing for the announcement of my candidacy

Here, I am pictured spinning thread with a huango. My family helped me take photos this day in preparation to announce my candidacy for Reina. Antonio Vacacela

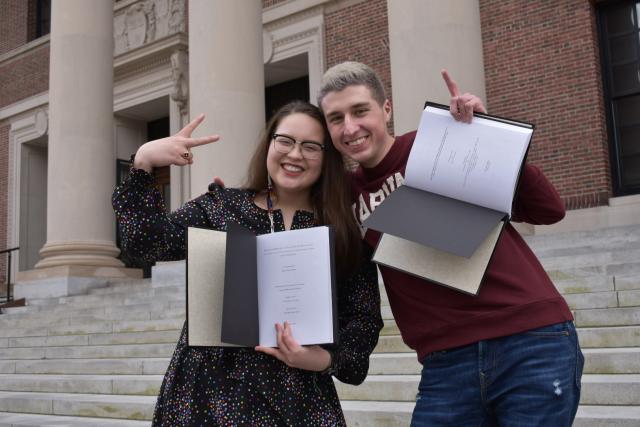

Over the course of a few weeks, I kept practicing every day after my classes and to hilar became a form of self-care at the end of the day. My family came to visit me in late September to give me a new huango, which I would use on the actual day of the competition, and I took my uncle and aunt on a tour of Harvard! We even visited Widener Library and I was able to show them the books I checked out which were written about the Saraguros in Ecuador.

Posing with my huango during the competition

In this photo, I am presenting my traje típico (traditional Saraguro clothing) with my huango in hand, as this portion of the pageant honors the ideal Saraguro woman. Antonio Vacacela

Learning Kichwa was one of the most difficult parts of preparing for the pageant, since my family has been affected by language loss due to discrimination and migration. My grandmother recalls being taught to not speak Kichwa in public, out of fear of violence and discrimination from even her school teachers, and my mother did not learn the language as a result. Thus, learning Kichwa basics such as how to introduce myself and greet others was a collective process of healing and remembering for my family. As we approached the pageant, we collaborated with my uncle in Ecuador to compose my introduction and I practiced the pronunciation and memorization with my grandmother.

Another part of my preparation involved learning how to present myself as a leader and intellectual, while communicating my vision for our community. It felt really amazing to reflect on my contributions to my hometown, high school, and community at Harvard, because I felt very prepared to advocate for myself as a leader.

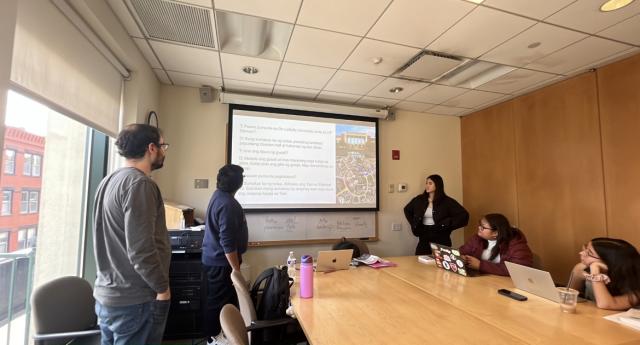

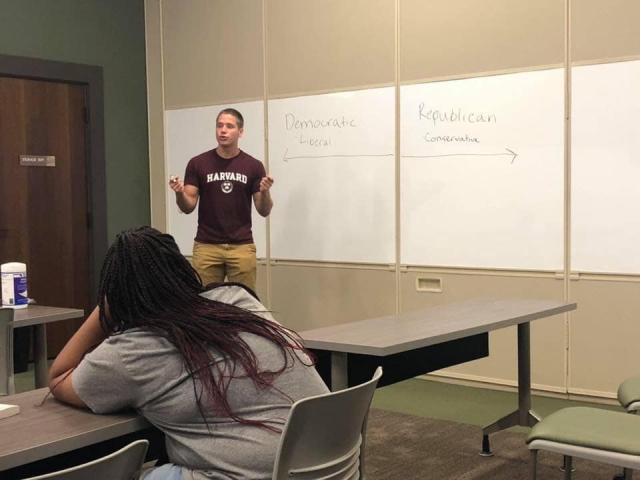

In these past two years, I’ve taken indigenous studies courses at Harvard that pushed me to reflect on indigeneity and cultural consciousness in the context of globalization and modernity. I prepared my answers to the questions (there were four possible ones) by incorporating my lived experiences, knowledge from my classes, and my family’s collective knowledge. It was empowering to be able to center indigenous knowledge and my own experience as a formerly undocumented immigrant, rather than hide behind my story as I had done before.

On the day of the pageant, I was the most stressed and anxious I have ever been! I felt incredibly prepared and ready to share my ideas with my community, after weeks of rigorous practice, but I was not used to facing a large crowd of people. In the moments during el hilado and the individual presentations in Kichwa, I felt the power of my ancestors, my family, and my friends take over my body. I almost felt paralyzed by the fear of performing in front of 500 Saraguros, but my passion to share from within gave me the strength and courage to continue.

On stage with the candidates

There were four young women competing in the election, representing Saraguros in New York, Massachusetts, and Wisconsin. Antonio Vacacela

Life moved in slow-motion when the judges announced the winner. There was an incredible effervescence in a room full of people who looked like me and shared the same history of struggle and resilience. I felt ecstatic to represent my family, especially my grandfather Jose Antonio Vacacela, who was one of the first Saraguros to migrate to the US. Lastly, it was the most fulfilling experience to share my passion with indigenous youth, who tuned into the broadcast from all over the world. We spent the rest of the night celebrating with all the Saraguros who came to support the event and bonding with the candidates and their families, who had come from Wisconsin, Massachusetts, and New York.

Posing with my role model and grandfather, Taita Jose Antonio Vacacela

I dedicated my success and performance to my grandfather, Taita Vacacela, who has continually sacrificed to provide for my family. Antonio Vacacela

In this next year, I will take on a leadership role within the Saraguro community in the US and begin my own initiative focused on indigenous youth wellness and mental health. This experience was incredibly transformative in helping me reclaim aspects of my culture, pushing me to grow intentionally as a person and leader, and inspiring my vision of where I want to fit in this world after graduation. I have felt personally rescued and invigorated by my personal journey with indigeneity and I hope to spread this message in my time as Reina SarUSA 2022-2023.

A moment in the spotlight

I never expected to be capable of posing and performing in front of a large audience, but the courage of my ancestors supported me the entire night. Radio Estilo24