When applying to colleges like Harvard, I was most excited to pursue opportunities that included research. Especially as a prospective Astrophysics concentrator (Harvard lingo for major), I was eager to jump into this world of exploring the universe through telescopes, data archives, and wet labs. As a current junior at the college, I’ve had my fair share of opportunities to fully immerse myself in research. Because Harvard is a research university, most concentrations offer abundant resources for undergraduate research. It’s typically as easy as sending an email.

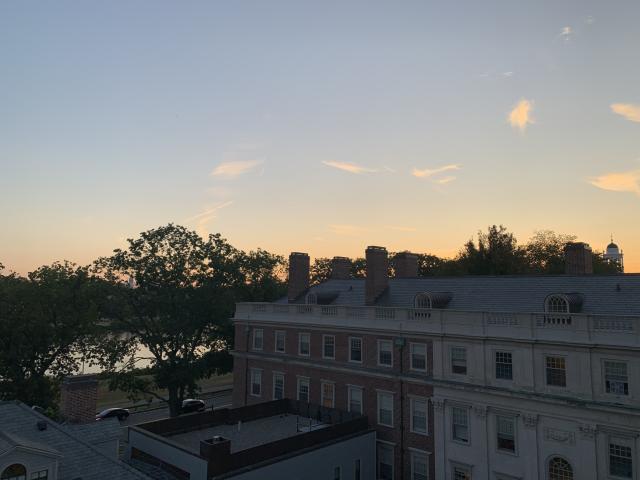

(Taking a stroll through the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, the site of astrophysics research at Harvard)

Before starting my freshman year, I received an email from the Earth and Planetary Sciences prospective mailing list. During this time I was considering studying Earth and Planetary Sciences, and I was eager to broaden my horizons and delve into a new field. I decided to participate in the EPS Short-Term Research Program, which provides students with an amazing opportunity to work on a Harvard research project for 3 weeks in the summer. I worked on two projects with the EPS department– the first one examined the mineral composition of the Martian interior, and in the second project I compiled and worked with data to study past ocean climates/chemistry in varying regions. I even got to meet a few other students in my class year, which made the process of starting college a bit less stressful.

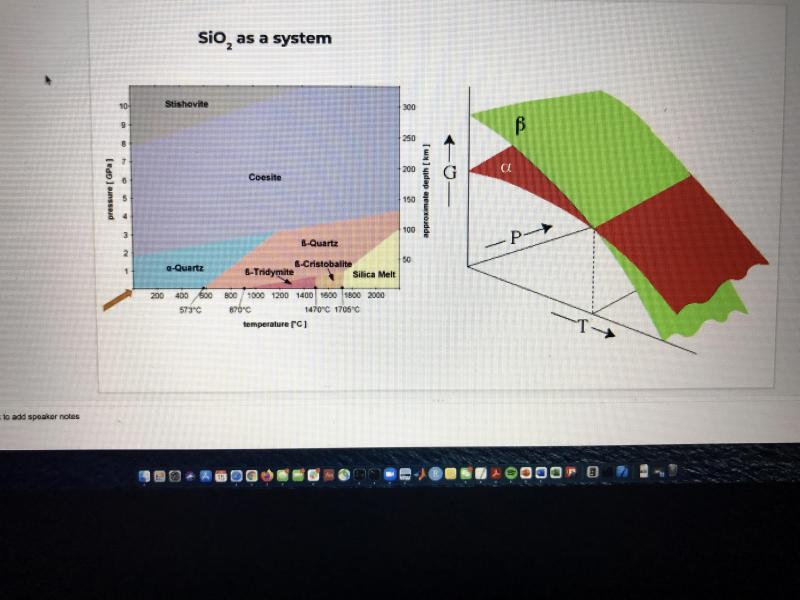

(Learning about different minerals that make up Mars during my EPS research program)

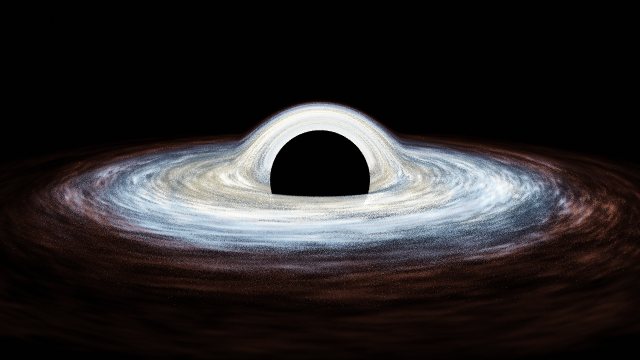

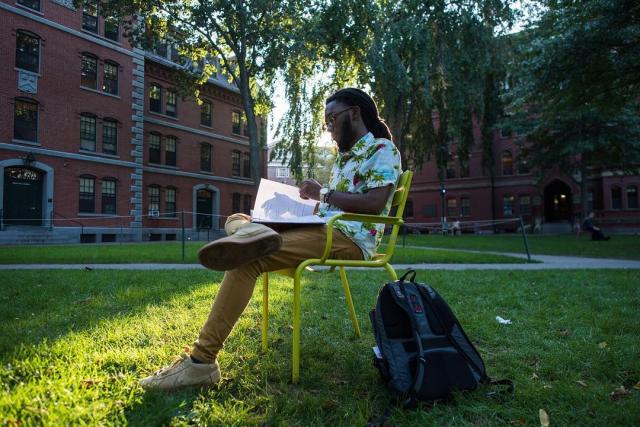

After my first semester in college, I decided to re-enter the research conversation. As a first-semester freshman, I had been advised not to do research, as it was important to become acclimated to college academics, and I did not want to overload myself. I was also eager to specifically begin astrophysics research at Harvard, as I had previously experienced research in a different field. Starting at the beginning of my second semester, I began to reach out to a few professors and researchers whose research sounded interesting, and I ended up beginning a project with Dr. Fabio Pacucci– a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Astrophysics and Black Hole Initiative. This led to a summer project, where I spent my summer as a PRISE (Program for Research in Science and Engineering) fellow. My project concerned studying two of the furthest galaxies ever detected before the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, and I even had the opportunity to present this research at the American Astronomical Society’s 240th Meeting in Pasadena, California!

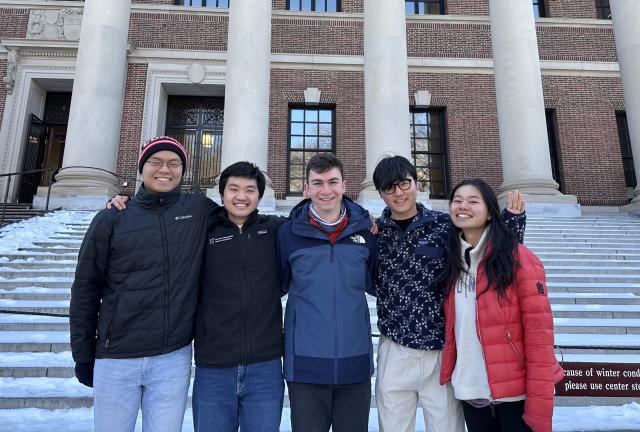

(My friends and me presenting at the 240th American Astronomical Society Meeting!)

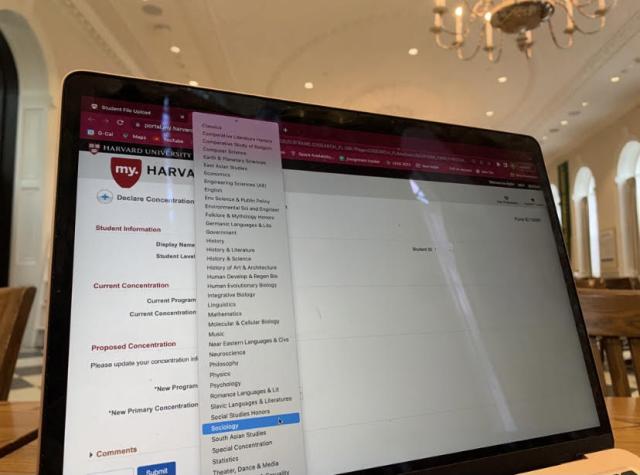

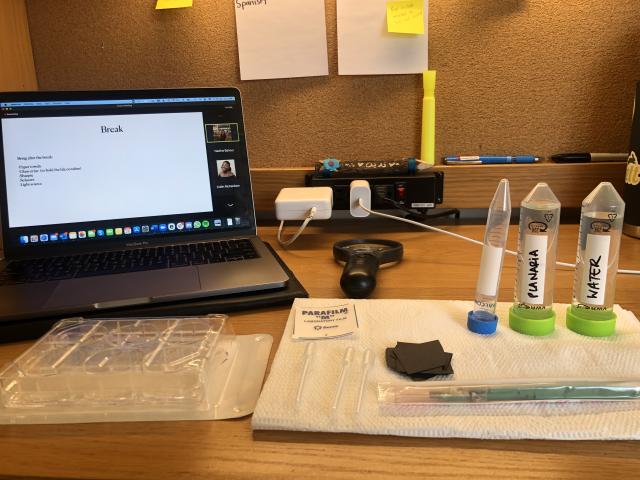

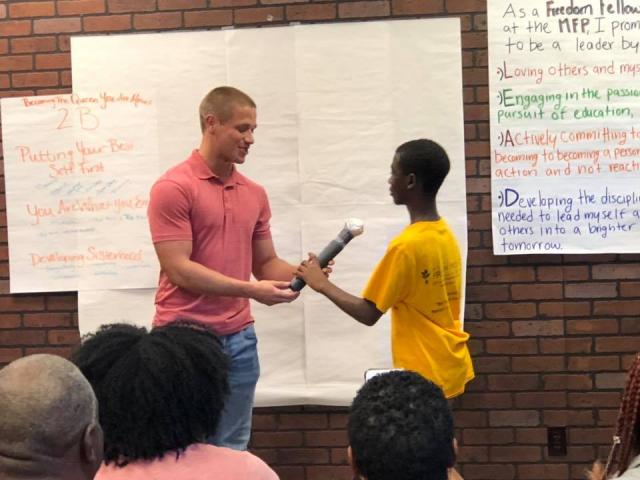

After a summer of highly theoretical research, I still felt a bit unsure about which direction I hoped to take in terms of my own research. With sophomore concentration declaration coming up, I was stuck between two concentrations to joint with Astrophysics (at Harvard you can combine two fields of study into one joint concentration!)– Earth and Planetary Sciences or Physics. Because my summer research was more on the physics side of astronomy, I decided to branch out and try a more involved Earth and Planetary Sciences research lab. All it took was a few emails to professors and labs that sounded interesting. The lab that most caught my eye was Dr. Robin Wordsworth’s Martian Habitability Lab. Dr. Wordsworth’s lab engineers low-tech microbial habitats that can withstand the more difficult conditions for life on Mars. After interviewing for the lab in the fall, I was granted a research assistant position! Thus began my semester in a wet lab– twice a week I would enter the lab and work on engineering and testing different microbial habitat solutions with my amazing post-doctoral advisor Dr. Jake Seeley. This was one of the most exciting research experiences I’ve had the opportunity to participate in at Harvard.

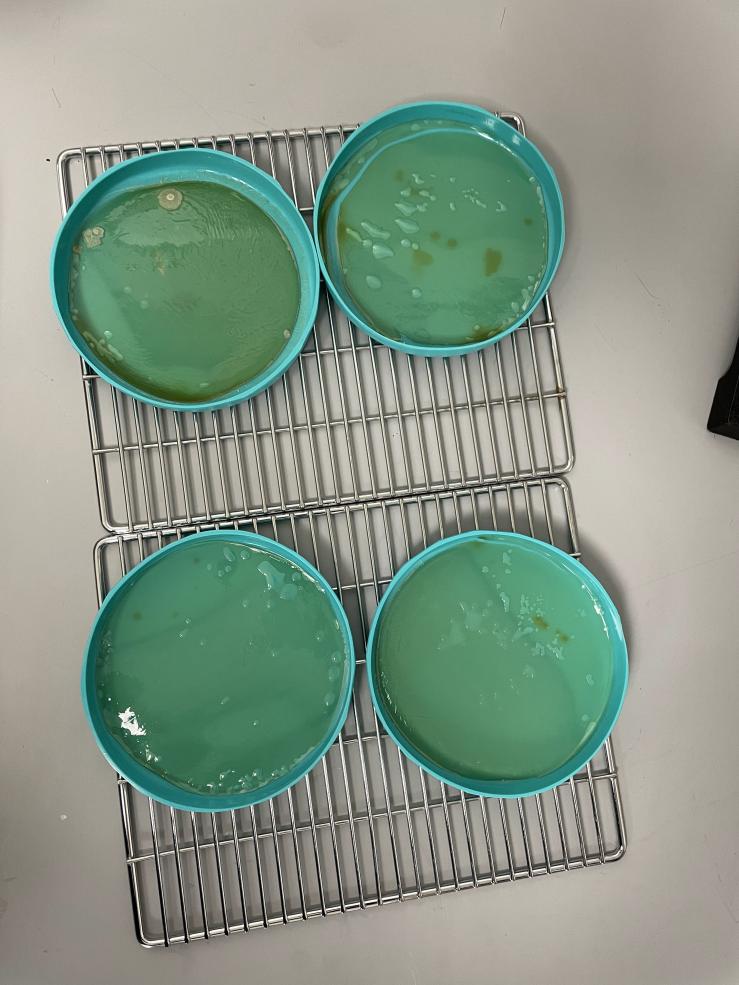

(Manufactured bioplastic materials from my lab!)

Entering my sophomore spring, I had planned to take a break from research. I was eager to continue my pursuit of taking advantage of Harvard’s resources, but I knew that this semester was going to be busy and I did not want to have too many commitments outside of classes. That’s when I discovered Astronomy 191: Astrophysics Laboratory. This class offered an opportunity to pursue research as one of my semester classes, offering a diverse array of projects and a field trip to the site where the Cosmic Microwave Background was first detected. The class was not a joke– it required intensely immersive research participation, writing two 20+ page research papers in one semester, and various presentations in front of astrophysicists at the forefront of their respective fields. Although looking back this class was the most time-consuming class I have taken at Harvard (20+ hours of work outside of class per week), it has by far been the most rewarding. The first project I worked on concerned studying star formation rates in two merging galaxies where we controlled the Submillimeter Array Telescope located in Mauna Kea, Hawaii to obtain data. From this data, we were able to reconstruct plots and graphs of the galaxy to better understand star formation and galaxy properties. I was also able to work with several renowned astronomers, including Dr. Qizhou Zhang and his group.

(My Astronomy 191 class at the Holmdel Horn Antenna, the site of discovery for the CMB!)

The second project I worked on over the semester was in the course director Dr. John Kovac’s lab. Our project concerned nuclear fusion in brown dwarf stars and recreating nuclear fusion in a laboratory setting. That’s right… we built a nuclear fusor. Within our fusor chamber, we introduced deuterium gas that we then charged to a high voltage. This arduous process allowed us to achieve deuterium fusion (essentially two positively charged deuterium nuclei merging)! This project took countless hours of lab time a week to get our apparatus working, and it ended with testing our apparatus at MIT to ensure its functionality. This project was truly a once-in-a-lifetime experience– how often do you come across the opportunity to build a literal nuclear fusor?

(My fusor chamber achieving deuterium-deuterium fusion, and me controlling the apparatus!)

After a long and arduous semester of research in Astronomy 191, I decided to take the summer off from full-time scientific research. I worked at Bryce Canyon National Park as an interpretive astronomy park ranger, continuing the first research project from Astronomy 191 (studying merging galaxies) part-time. At Bryce Canyon, I did research on native star stories in different cultures, celestial navigation, and dark sky preservation, giving talks on these subjects to public audiences and park visitors. This was definitely a different type of research than I’ve done in the past– in astrophysics, most research focuses on new scientific findings, so having the opportunity to approach astrophysics through an anthropological and historical lens was an amazing opportunity.

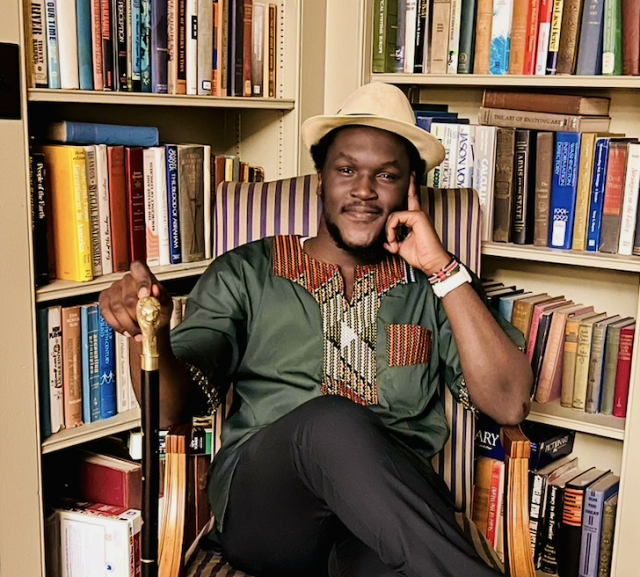

(Me giving my presentation on cultural star stories at Bryce Canyon National Park!)

Now as a junior at Harvard, I am currently taking Astronomy 98, the junior thesis research tutorial in astrophysics. In this class, we do a semester-long research project and present our findings to astronomers at the Center for Astrophysics, similar to Astronomy 191. For my junior thesis tutorial, I am working with the Submillimeter Array group from Astronomy 191 on a separate project involving merging galaxy star formation and carbon-monoxide line ratios to better understand merging and high-energy environments. With the support of my advisors Dr. Qizhou Zhang and Dr. Jakob den Brok, my research experience has been nothing short of incredible. Looking back at these experiences, I am so grateful for the depth and breadth of research that I’ve been able to explore as an undergraduate student. As a research university, Harvard provides access to unparalleled opportunities for students to work with scientists at the forefront of their fields. Although research is definitely not easy, and I have found myself up in the early hours of the morning writing research papers or debugging code for my next group meeting, I am beyond grateful for all of the projects I’ve been able to participate in. My draw to astrophysics research comes from the opportunity to discover the universe's greatest physical mysteries. However, with any type of research, you have the opportunity to begin piecing together science’s greatest puzzles with the support of amazing faculty– I recommend taking advantage of it!

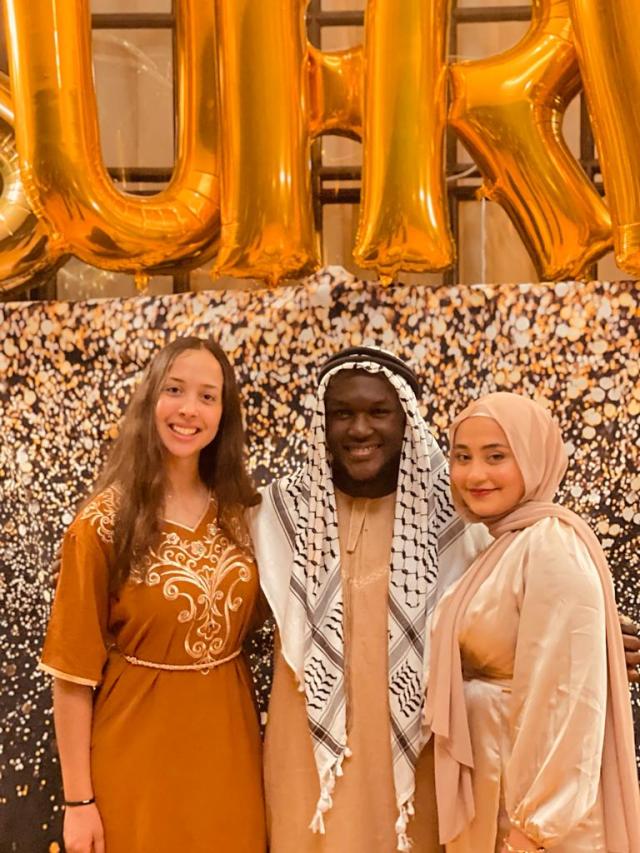

(Friends and me outside of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian!)